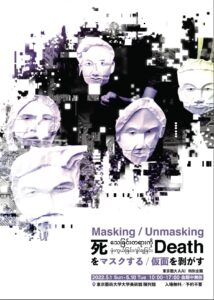

Pick Up (2022/05/15)|Exhibition “Masking/Unmasking Death”| Rina Tanaka

Tokyo Geidai AAI Special Exhibition

Tokyo Geidai AAI Special Exhibition

“Masking/Unmasking Death”

Chinretsukan Gallery, The University Art Museum, Tokyo University of the Arts

May 1 to May 10, 2022 (Date of visit: May 2)

→展覧会「Masking / Unmasking Death 死をマスクする/仮面を剥がす」

Text by Rina Tanaka

Photo by UPN

Organizers: Graduate School of Global Arts (GA), Tokyo University of the Arts Yoshitaka Mori Lab, Tokyo University of the Arts Global Support Center – Tokyo Geidai Asia Art Initiative (AAI), UPN, Ltd.

Supported by: Arts Council Tokyo (Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture), Kao Foundation for Arts and Culture

Curator: Haruka Iharada

Artist: Kamizu

Project cooperation: TERASIA

—

Exhibition “Masking/Unmasking Death”

This special exhibition at the Tokyo University of the Arts displayed 100 paper masks that portray the faces of those whose lives were deprived since the military coup began in February 2021. Kamizu, an artist from Myanmar, has created these works, maintaining herself anonymous for safety reasons.

The exhibition consists of three key players: the Tokyo Geidai Asia Art Initiative (AAI) of Tokyo University of the Arts, Haruka Iharada, and the transnational art project “TERASIA | Theater in the Age of Isolation”—Christian Cicogna and I reviewed two productions born from this project, TERA เถระ (Thailand, 2020) and Tera in Kyoto (Kyoto, 2021) in the previous issues (I am also involved in TERASIA as an external observer(1)). Taking part in TERASIA in 2020, Kamizu sought a way to present her production. TERASIA’s members in Japan, which include alumni from Tokyo University of the Arts, connected her to Iharada and the AAI. Kamizu’s works finally succeeded in coming to Tokyo in the form of an exhibition(2).

Facing “Fallen Heroes”

On the second floor of the Chinretsukan Gallery, there was a white room with a high ceiling and some depth. A white lake made of paper spread out in the center, surrounded by several white nets. Paper trees were also settled on the backside of the room.

There was a timeline from February 2021 to the present on the wall next to the entrance. A screen showed a video message from Kamizu. Her face was also masked by animation.

Inside each white net, I found six to seven masks of “Fallen Heroes.” On the floor, I also found the same number of QR codes as the masks. Once I read them with my smartphone, I reached information in three languages (Burmese, Japanese, and English), corresponding to each mask: the name, gender, age, date and place of death, occupation, cause of death, and a photograph of each face in their lifetime. Some “heroes” were severely tortured. Some corpses were damaged. Some died just last month.

When I looked up and tried to find the mask corresponding to the information that I had just read, sometimes I felt that the black eyes drawn on the paper mask stared at me. Hundred paper masks were no longer a collection of works but emerged as an assembly of individuals. The exhibition room transformed into a space of mourning.

Objets d’art also created the space of mourning based on Myanmarese rituals. The white “net” is to cover a dead body on the bed in a funeral ceremony. The “lake” is a symbol of purification and reincarnation. Kamizu explained that she created the “lake” as a place where “fallen heroes” can rest in their afterlife and where visitors can face and think about death(3). Visitors can also write down their thoughts on cards or masks in the room (In this regard, three workshops were held to dialogue with Kamizu. She appeared in the exhibition space through the Internet).

Mourning, Co-presence, Pray

Clearly, this exhibition showed resistance to the military coups in Myanmar. However, it did not intend any rapid social change, nor can we disassociate ourselves from the work. Rather, this is a method of survival for the artist, who faced numerous deaths in the military coup and was not able to go through without creating their masks. At the same time, the exhibition functioned as a ritual to regain the human dignity of each victim, who has been often quantified and anonymized, by the co-presence of others who stay with the artist’s mourning in a shape of masks. Therefore, the exhibition space is for a political and social act while offering an intimate experience.

(ကြုံသလေဘုံဘွေ, Performance: Kyojun Tanaka; Audio recording: Miho Miura, Nao Nishihara; Videography: Ryohei Tomita; Concept: TERASIA)

In this regard, I would like to mention a video posted on May 7, 2022, by the official Facebook account of the exhibition(4). The video showed a solo performance of the hsaing waing, the traditional Burmese orchestra, by Kyojun Tanaka. The soft, enfolding tones of the maung hsaing, a set of bronze gongs, sounded like a prayer. A triangular structure works here: the artist mourned for the dead, the musician listened to it by playing, and viewers in different times and spaces witnessed the musician’s co-presence with the masks at the exhibition space, as if they would visit a temple and peek inside the main hall where the ceremony takes place.

The rituality in the exhibition space does not mean that this exhibition forced visitors to be involved in the ritual act of the artwork. When visitors would read a commentary on Myanmar’s political situation on the wall and access the victims’ personal information with the individual smartphones, they would interpret them as a strong statement. However, I should note that the exhibition did not simply request any solidarity or support as in the demonstration. Instead, it contains an earnest desire to “accept the desperate realities and think together about a line that turns them into hope.”(5)

Answer to the Questions

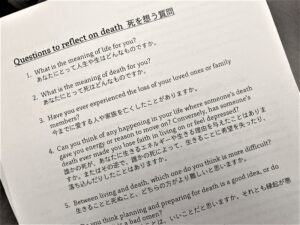

At the corner of the exhibition room, there was a paper of “Questions to reflect on death” that visitors could take home. This list of questions was not directly connected to the military coup but rather let visitors think of death individually. The questions include: “What is the meaning of life for you?”, “Have you ever experienced the loss of your loved ones or family members?”, “Can you think of any happening in your life where someone’s death gave you energy or reason to move on? Conversely, has someone’s death ever made you lose faith in living on or feel depressed?”

The list of questions reminded me of the scene of 108 questions and answers in the three “sister” theatrical works born from the project TERASIA—Tera, TERA เถระ, and Tera in Kyoto. In the scene, the performer(s) holding a percussion instrument in one hand verbally ask(s) the audiences simple and sometimes philosophical questions about life and death. The audiences quickly answer to each question by (not) making an individual sound with percussion. A volley of questions and answers turns into impromptu music between the performer(s) and the audiences. Although the audiences almost have no choice but to participate in it, the scene can create a playful chorus by using percussion that remains each answer anonymous and keeps the volley in a good tempo.

Since “Masking/Unmasking Death” is the part of the project TERA, “Questions to reflect on death” may be a different form of the 108 questions and answers. However, not all visitors took this question list, nor were they necessarily requested to share the answers with others. Rather, the questions supported visitors willing to reflect on death whenever they wanted. In this respect, “Questions to reflect on death” carried out the key concept of this exhibition: solidarity by thinking in individual ways, but they may cross each other.

Staring at a multifaceted expansion of the exhibition

In “Masking/Unmasking Death”, visitors can also tape a message card on the “trees.” After several days, the “trees” became full of cards. The language and content of the message were varied, from “no war” and “against violence” to frankly stating personal views of life and death. It was quite different from message boards in some art exhibitions, on which I often saw very monotonic, “seemingly correct” answers.

“Masking/Unmasking Death” is an exhibition with multiple facets. It is not easy to appreciate it as one single artwork with conventional artistic autonomy. Meanwhile, if you would visit the exhibition in order to get some ethical answer, or if you would like to interpret it as a mere social movement, the multi-layered essence of this exhibition would be easily lost. Art does not give a direct prescription for social events, nor does it drive us towards one clear and correct answer. Once the visitor would treat the work in that way, it could lose its value as art. And if there is any artwork that functions in that way, it is something else wrapped in art’s clothing.

The wish to “accept the desperate realities and think together about a line that turns them into hope” warns us who tend to abandon thinking by ourselves and float on plausible opinions. Of course, it never is easy to heed times and spaces that are not here and now through appreciation of an artwork while not leaving behind yourself as who experiences the art. However, in the times of art crisis today, we urgently need another way, instead of taking an objective distance to the artwork, instead of sympathization with ignoring differences between oneself and what was depicted in the work. To detour when lines are blocked. To stop and think not alone. It is “hope” not only for them, but for us too.

(2022/05/15)

—

(1) Rina Tanaka「TERASIAに外部観察者として関わるとはどういうことか?」『TERASIA テラジア|隔離の時代を旅する演劇』、November 23, 2021.

(2) Haruka Iharada, “Curator message: To Overcome Despair” (The cited text was translated by the author from Japanese handout at the exhibition; The English handout is available in the official website with slightly different nuance from the Japanese one).

(3) Cited from captions at the exhibition.

(4) According to the posts on the Facebook Page “Masking/Unmasking Death” on May 7, 2022 and on YouTube on May 10, 2022。

(5) Iharada, “Curator message.”