Paintings from Siberian Memory — Goro Shikoku and Yasuo Kazuki — | Nobuyuki KAKIGI

Paintings from Siberian Memory

— Goro Shikoku and Yasuo Kazuki —

Text by Nobuyuki KAKIGI

Photos are courtesy by Nerima Art Museum

One of the origins of Goro Shikoku’s postwar painting career is that he was interned in Siberia. He had been drafted into the army at the end of the Asia-Pacific War and sent to the front lines in northeastern China. After Japan’s unconditional surrender, he was held captive by the Soviet-Russian army. Between forced labor, Shikoku was involved in activities to create wall newspapers and picture story shows with his camp comrades. Later, the poet-painter recalled that the production of “Tsuji-shi (Street Poem)”, in which anti-war and anti-nuclear messages were accompanied by pictures, was an extension of his activity in Siberia. Under the occupation, Shikoku, the poet of “Atomic Bomb Poems” Sankichi Toge, and others posted “Tsuji-shi” works on the streets in a guerrilla-like way, to call for peace. In the mid-1970s, Shikoku made an effort to collect “A-bomb Drawings by Survivors”.

In Shikoku’s painting “Ruins of the Atomic Bomb are Vanishing” (1990), which expresses his worry about the destruction of atomic bombing remains in the process of urban development, appear soldiers who died in the war looking at the present from the sky with the victims of Hiroshima. Such depiction cannot be understood without his experience from his call-up to his demobilization in 1948. Shikoku must have been looking at the reconstruction of Hiroshima, linking death on the battlefield and death by the atomic bomb from the perspective of war — there were major army bases in Hiroshima, and the city was “military capital” until the atomic bombing. I was reminded of this when I saw the “Goro Shikoku: A Message of Peace” exhibition in Hatsukaichi, Hiroshima Prefecture.

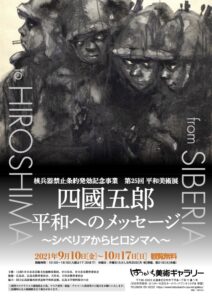

The exhibition, also titled “From Siberia to Hiroshima”, was held at the Hatsukaichi Art Gallery (September 10–October 17, 2021) as a “Peace Art Exhibition” to commemorate the entry into force of the Treaty on Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (January 22, 2021). In the exhibition, Shikoku’s “Bean Diaries” were on display. In this tiny notepad, the harsh conditions of life in the extremely cold camps are described with line drawings in detail. It is said that he took this diary home with him, concealing it in his military boots. If Soviet-Russian soldiers had found it, he could have been charged with espionage. Shikoku risked his life to carry with him memories of his internment to Hiroshima, which had been devastated by the atomic bomb.

In the process, the image of the soldier who failed to return to his hometown may have been burned into the mind of this poet-painter. And the images of these memories that emerge when he paints “for peace” seem to have been visual. The soldier figures that appear in the works mentioned above are also clearly figurative, as in the work depicting his visit to the site of the Siberian internment camp in the late 1990s, in which he depicted the current landscape of the site under a bird’s-eye view composition that suggests the perspective of the dead. In this painting, the visiting group, including him, is depicted with the soldiers who lost their lives there with clear human figures.

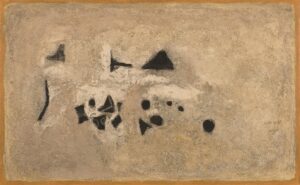

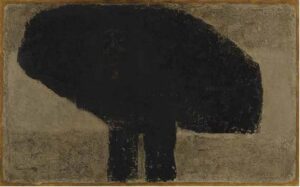

Yasuo Kazuki, who also experienced Siberian internment and continued to depict his memories in the “Siberia Series” after the war, seems to recall his experiences in the camps in a tactile way, unlike Goro Shikoku, who remembered his life in internment through visual images, including line drawings in his “Bean Diary”. For example, “To the North, to the West” (1959), condenses anxiety and frustration of prisoners of war, presumably including the artist, those who were crammed into a train that left Mukden without being told its destination, by abstraction in sculptural three-dimensionality. The artist seems to be trying to carve out the anguished faces from the unique black-based painting, especially from the thoroughly matted black.

One of the reasons behind Kazuki’s attempts to capture his memories with his hands in this way may have been the fact that his sketchbook, in which he had sketched portraits of his camp comrades, was taken from him by the soldiers guarding the camp. Nevertheless, this did not cause him to forget the faces of his comrades. In “To the North, to the West” and “River Amur” (1962), both of which also depict a group of people, the faces of each individual are different from the others. Looking at the latter work, in particular, the turmoil and despair of those who have been driven from different parts of the Japanese archipelago come from different directions. They are facing the decisive break that crossing the river Amur will bring.

These and other works from the “Siberia Series” were exhibited in the chronological order of their creation at a retrospective exhibition commemorating the 110th anniversary of the birth of Yasuo Kazuki (Nerima Art Museum, Tokyo, February 6, 2022–March 27, 2022). According to the explanation accompanying the exhibition, “Hulunbuir” (1960), inspired by the scene of animal bone fragments scattered in a meadow, was created after the inspiration had been sculpted into a three-dimensional work. Kazuki was also trying to grasp the composition of the picture plane based on his mental landscape with his hands. The painting based on this attempt shows barely visible bones of animals with horns scattered about, but their gloomy abstraction and flatness also evoke the bloodstains of human corpses.

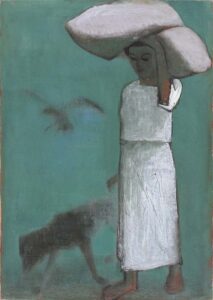

This exhibition, which provides an overview of Kazuki’s artistic activities, also reveals that even before he began working on the “Siberia Series”, he was sculpting to grasp his subjects. In the case of “Woman Carrying” painted in 1943 when he was drafted into the army, a wooden sculpture of the woman was left behind. The artist himself considered drawing as a way of knowing things through the sense of touch, and in the “Siberia Series”, he was attempting to carve out an object as a mental image. The face of the “Woman Carrying” emerges from the greenish-blue ground, and in the backlight, it seems that she is stifling her emotion as if she is withdrawing inward, which seems to have strengthened the tranquility of the picture.

Looking at “Woman Carrying” after seeing the “Siberia Series”, one is reminded of “Man Carrying” (1960), which depicts a prisoner who becomes one with the burdens he is forced to carry. In this work, the face of the prisoner is painted in a frontal portrait so that the face, etched with the painstaking labor of the prisoner, comes to the fore. But the artist also left a drawing of the “Man Carrying” from the side, as if he were a dromedary. This also indicates that Kazuki was trying to capture the human way of life in his memory in a tactile, three-dimensional way. In this tactile recollection of his Siberian experience, the past may have returned more directly to the artist’s body.

Unlike the sense of sight, which is linked to cognition, the past is recalled as an event in the sense of touch. After going through the extreme conditions, Kazuki’s body seems to have unexpectedly and vividly recalled the Siberian experience from the inside. To counteract the intensity of these memories and accept that it is not the past itself that is recalled, but rather the memories of the past, he may have composed his paintings with a unique abstraction in the reduced colors and formed faces without direct expression of emotion. The exhibition also showed that the facial features in Kazuki’s paintings were formed under the influence of the religious statuary of medieval Europe, which he saw during his visit to Europe in the mid-1950s.

Perhaps painting directly on a religious theme, as in “Nirvana” (1960), was one way for the artist to sublimate the unorganized memories that welled up in his mind. However, when one stands in front of the painting in which mourning faces emerge over the remains of dead comrades, we can feel the sorrow mixed with fear of our own tomorrow’s fate emanating from every face in the present moment. At the same time, we notice that in such works, Kazuki has added a unique sense of fantasy to his paintings by placing himself in the past, or rather, on the side of the dead.

One work that might be a striking example of this point is “Blue Sun” (1969). The artist states in the commentary to his work that this painting depicts a view of the noontime, starry blue sky from the depths of a Siberian ant burrow, but it can also be thought of as a view of that sky from the orbits of the dead, killed like ants. In this work, the sky is represented in a brilliant pale blue. The exhibition concluded by showing that the artist was breaking new ground by opening his paintings to color at the end of his life. It also tells that his unique style was based on a tactile method different from that of Goro Shikoku, who also experienced Siberian internment.

On the other hand, through this exhibition, I realized that Kazuki’s works have the power to provoke thought under the current circumstances. For example, in “Imprisoned” (1965), which depicts the face of a soldier watching over prisoners of war from a surveillance window, the guard appears to be more confined to his cell. On the wall of the guard room is a sickle and hammer, the symbol of the Soviet Union. This work, which shares a composition with the early work “Gate, Stone Wall” (1940), may show the vacant face of those who are entrapped by the overall mechanism. The painting asks how to confront this face that is forced to fight amid the war that is going on right now.

Exhibition Websites

https://www.hatsukaichi-csa.net/galleryevent/heiwaten_shikokugoro/

https://www.neribun.or.jp/event/detail_m.cgi?id=202110291635493767