Listening to the voices in Asia: A Review of Asia Orchestra Week 2022, Tokyo|Haruka Kanoh

Listening to the voices in Asia: A Review of Asia Orchestra Week 2022, Tokyo

Listening to the voices in Asia: A Review of Asia Orchestra Week 2022, Tokyo

Text by Haruka Kanoh

Photos by Fumiaki Fujimoto,

provided by Association of Japanese Symphony Orchestras

>>>Japanese

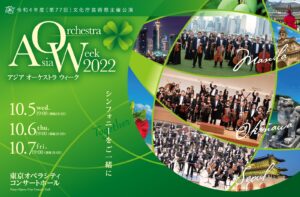

Asia Orchestra Week (AOW) was held at Tokyo Opera City Hall from October 5th to 7th, 2022. AOW is a series of projects started in 2002, and from 2007 onwards, organized as a sponsored performance at the National Art Festival, Agency for Cultural Affairs. The legacy of AOW has continued for 20 years, with the exception of 2020, and invited only domestic orchestras in 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The year 2022 was the first AOW that included foreign orchestras after the gap of two years. The participants were: the Manila Symphony Orchestra (MSO) from the Philippines, the Ryukyu Symphony Orchestra (RSO) from Okinawa, Japan, and the KBS Symphony Orchestra (KBSSO) from Korea. I had the opportunity to listen to all three concerts. In the following section, I would like to review the concerts of the MSO and the KBSSO, followed by a review of the RSO in the next section, and conclude with my opinion acquired through this event.

***

When comparing the orchestras that one usually does not get a chance to enjoy, the contrast between the tones of the MSO and those of the KBSSO impressed me to the maximum. The MSO’s sounds were extremely soft and mild even when they performed the symphonic poem “Lahing Kayumanggi” (“Brown Man” in Tagalog), illustrating the Philippines’ history of hardships from pre-colonial times to its independence. The sounds of the KBSSO, on the other hand, were so clear and honest even in the overture to “Die Fledermaus” (Johann Strauss II). I assumed some influence of culture, society, or musical education system in each country if not reduced to essentialism.

When comparing the orchestras that one usually does not get a chance to enjoy, the contrast between the tones of the MSO and those of the KBSSO impressed me to the maximum. The MSO’s sounds were extremely soft and mild even when they performed the symphonic poem “Lahing Kayumanggi” (“Brown Man” in Tagalog), illustrating the Philippines’ history of hardships from pre-colonial times to its independence. The sounds of the KBSSO, on the other hand, were so clear and honest even in the overture to “Die Fledermaus” (Johann Strauss II). I assumed some influence of culture, society, or musical education system in each country if not reduced to essentialism.

The audience enjoyed the performance of the conspicuous young soloists from each of the countries, which showed the prominent presence of Asian musicians in the present global standard of classical music. Kim Bomsori, a violinist with substantial experience in playing worldwide, performed with complete energy and brilliance. The soloist for the MSO was Damodar Das Castillo, a cellist born in 2007 in Manila. When he appeared on the stage of AOW, he appeared like an innocent boy, but his first several sounds held the audience spellbound. He put all his soul into his musical instrument and sometimes exploded his expression as if he was possessed by his cello.

The audience enjoyed the performance of the conspicuous young soloists from each of the countries, which showed the prominent presence of Asian musicians in the present global standard of classical music. Kim Bomsori, a violinist with substantial experience in playing worldwide, performed with complete energy and brilliance. The soloist for the MSO was Damodar Das Castillo, a cellist born in 2007 in Manila. When he appeared on the stage of AOW, he appeared like an innocent boy, but his first several sounds held the audience spellbound. He put all his soul into his musical instrument and sometimes exploded his expression as if he was possessed by his cello.  The powerful performance was assisted by the mild sounds of the orchestra, all of which were softly unified under the directions of the conductor. His solo encore “Transcendence” (composed by Faye Miravite) was a unique performance combining his cello and simple voice. The repeated short phrases, the meaning of which might not be understood by most in the audience, were refraining like a prayer.

The powerful performance was assisted by the mild sounds of the orchestra, all of which were softly unified under the directions of the conductor. His solo encore “Transcendence” (composed by Faye Miravite) was a unique performance combining his cello and simple voice. The repeated short phrases, the meaning of which might not be understood by most in the audience, were refraining like a prayer.

In the three days of the concerts, in terms of works, Isang Yun’s Symphony No.2 left the biggest impression on me. Isang Yun studied cello and composition in Japan during the colonial period, but was imprisoned for his participation in the resistance movement. After the war, he was imprisoned and tortured by the South Korean military regime on suspicions of spying for North Korea; after his release, he became a naturalized German citizen in 1971. He died in Germany in 1995 without visiting his homeland ever again. Under the Kim Dae Jung government, all the restrictions around his works were lifted and his compositions began being performed more frequently. However, under the Park Geun Hye government from 2013, he became the target of blacklisting, and the budget for the Yun Isang International Music Competition was cut off (Chang 2020). Though I am unaware of the present scenario regarding his works in South Korea, KBSSO performed his Symphony No.2 in this historical, societal, and political context.

The KBSSO’s rendition showed the dynamics of music with clear frames. The multiple parts jostled with each other in the first movement, they were temporarily mediated in the second, and were followed by the third, creating mutual recognition and coexistence. It seemed as if the composer who was torn between West and East, Germany and Korea, and even between the divided country, was complaining about the violence of division and trying to gently integrate himself. The music ended with a quiet mood, and it led me to think about something.

The KBSSO’s rendition showed the dynamics of music with clear frames. The multiple parts jostled with each other in the first movement, they were temporarily mediated in the second, and were followed by the third, creating mutual recognition and coexistence. It seemed as if the composer who was torn between West and East, Germany and Korea, and even between the divided country, was complaining about the violence of division and trying to gently integrate himself. The music ended with a quiet mood, and it led me to think about something.

Immediately after the performance ended, two encore works were presented in a cheerful mood and they changed the atmosphere in the concert hall into a celebration. Although, it succeeded in enthusing the audience at the end of the concert as well as of the AOW, it was rather shocking because it seemed as if we, by clearing away the quiet mood that I mentioned above, somehow violently shut our ears to Isang’s message. This is not just a concern in Korea, where Isang and his works were restricted and excluded. He had expressed the absence of hostility towards present day Japanese people, but simultaneously, he noted the necessity for North and South Koreans to overcome the pain of the Japanese colonial era, and build true friendships in Japan (Yun and Rinser, 1981). His statement reminds us that, the concert’s Japanese audience were also a part of his works’ historical context, and therefore, should have listened to his voice more carefully.

***

So far, this article focused on the MSO and the KBSSO concerts. Turning to the RSO concerts, Ryukyu is another name for Okinawa, the southeast island in Japan. This orchestra was invited to AWO this year because it is the 50-year anniversary of the reversion of Okinawa to Japan in 1972. Okinawa in modern and contemporary Japanese history, has had a complicated past. Many people in Okinawa died or were injured in the Okinawa battle during WWII to save the mainland of Japan, and it continued to be under the US until 1972, although Japan gained its independence in 1951 with the Treaty of Peace with Japan. Now, 50 years after its reversion, approximately 70% of the total area of the U.S. military facilities in Japan is concentrated in Okinawa, which accounts for only 0.6% of the country’s land area, causing repeated military aircraft accidents in city areas. Okinawa people have openly shown their opposition to the landfill work at Henoko for constructing a new US base, but the Japanese government is enforcing the construction. Mainland Japan has continued to force the military burden on Okinawa under structural discrimination for many years. The 50-year anniversary must be commemorated to include all these issues. The AOW that is sponsored by the government and organized in Tokyo cannot celebrate the anniversary with naïve blessings.

So far, this article focused on the MSO and the KBSSO concerts. Turning to the RSO concerts, Ryukyu is another name for Okinawa, the southeast island in Japan. This orchestra was invited to AWO this year because it is the 50-year anniversary of the reversion of Okinawa to Japan in 1972. Okinawa in modern and contemporary Japanese history, has had a complicated past. Many people in Okinawa died or were injured in the Okinawa battle during WWII to save the mainland of Japan, and it continued to be under the US until 1972, although Japan gained its independence in 1951 with the Treaty of Peace with Japan. Now, 50 years after its reversion, approximately 70% of the total area of the U.S. military facilities in Japan is concentrated in Okinawa, which accounts for only 0.6% of the country’s land area, causing repeated military aircraft accidents in city areas. Okinawa people have openly shown their opposition to the landfill work at Henoko for constructing a new US base, but the Japanese government is enforcing the construction. Mainland Japan has continued to force the military burden on Okinawa under structural discrimination for many years. The 50-year anniversary must be commemorated to include all these issues. The AOW that is sponsored by the government and organized in Tokyo cannot celebrate the anniversary with naïve blessings.

The RSO concert at AOW neither focused on the political matters mentioned above nor did it “celebrate” the anniversary like a festival. In the first work of the day, “Kajadefu,” the Ryukyu traditional music and orchestra intertwined, and the traditional dance with delicate movements complimented it. The sounds and movements proceeded from the beginning to the end without an obvious story development. The second work, “In the Golden Forest” was composed by Haginomori Hideaki under the commission of the RSO. It described the forest of Yambaru (an area in northern Okinawa) as the hope for peace, demonstrating a future-oriented vision. Followed by Ravel’s piano concerto, the twinkling piano sounds by Hagiwara Mami produced light and exquisite music with the orchestra. This performance seemed to sublimate the cultural richness of Okinawa and the hope for the future.

The RSO concert at AOW neither focused on the political matters mentioned above nor did it “celebrate” the anniversary like a festival. In the first work of the day, “Kajadefu,” the Ryukyu traditional music and orchestra intertwined, and the traditional dance with delicate movements complimented it. The sounds and movements proceeded from the beginning to the end without an obvious story development. The second work, “In the Golden Forest” was composed by Haginomori Hideaki under the commission of the RSO. It described the forest of Yambaru (an area in northern Okinawa) as the hope for peace, demonstrating a future-oriented vision. Followed by Ravel’s piano concerto, the twinkling piano sounds by Hagiwara Mami produced light and exquisite music with the orchestra. This performance seemed to sublimate the cultural richness of Okinawa and the hope for the future.

The program’s first half left me with two questions: In commemoration the 50-year anniversary, would the program be too future-oriented leave the political problems behind? Then, how will Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No.5 work after these future-oriented performances? Finally, the final part of the fourth movement opened my eyes at once. Tchaikovsky’s deep and magnificent music sounded as if singing about the war, the occupation, and the base issues in Okinawa. Thereafter, the theme of destiny toward the end seemed to express the will to make a better future. In other words, the music composed in Imperial Russia appeared in front of me, to speak of present day Okinawa and Japan.

This concert seemed to give form to the thoughts of the music director of RSO, Otomo Naoto, who tries to cope with the political matters related to Okinawa, and, at the same time, sees great potential in music as pure entertainment.

***

For 20 years, AOW has offered the opportunities to enjoy the performances and works of orchestras from Asian and Pacific areas. In my view, AOW has continued to inspire audiences to think about the meanings and possibilities of classical music in Asia by organizing concerts for orchestras from Asia-Pacific under the name of “Asia.” The relations between Western countries, Asian countries, and Japan, might be a cause of continuous concern.

It is possible to consider AOW as the practice of Mari Yoshihara’s thought: “Asians’ remarkable achievements in classical music require reconsideration of the seemingly natural connection between the music’s European origin and the music as it is practiced today” (Yoshihara 2007: 227). From this point of view, three nights’ concerts showed some fragments of the rich, varied, and complicated relations not only with Asia but within Asia, from the past until the present. Asia cannot be explained by the simple idea of “Pilipino,” “Korean,” or “Japanese” music, but is generated by the complex relationship among countries, regions, and people. Here, classical music became the medium for Asia to think about Asia without being “the cultural outsiders” to the West.

To make classical music work as a medium for Asia, in my opinion, two perspectives are required to make it work. First, for the Japanese in general, it is important to be conscious of the position of “Japan” in Asia by remembering that the Empire of Japan ruled both the Philippines and Korea in the past, and that many Japanese classical music lovers used to feel, or still feel, superior to other regions in Asia. These issues should be continuously discussed. Second, Asia’s complex image shown by this year’s AOW also reminded me of the perspective that, every audience should be aware of their personal positionality towards each musical work, composer, performer or performance. In my case, being aware of my position not only as “Japanese” but also as a person who was born and raised in Mainland Japan, as well as a person who is currently at AOW and part of an audience enjoying music in Tokyo, would enable me to acquire a more careful understanding of music. I would like to conclude with the hope that, by reflecting on one’s own positionality and straining one’s ears towards the messages conveyed through the performances, classical music would not only become a medium to understand Asia, but also a more creative medium for making a bright future for Asia.

Reference

Asia Orchestra Week. 2022. Concert program.

Chang, H.K.H. 2020. Yun Isang, Media, and the State: Forgetting and Remembering a Dissident Composer in Cold-War South Korea. Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 18 (19).

Otomo, Naoto. 2020. 『クラシックへの挑戦状(Challenge to Classical Music)』中央公論新社.

Okinawa Prefecture. 2020. 「沖縄から伝えたい。米軍基地の話 Q&A Book(Message from Okinawa about the US Base)」(https://www.pref.okinawa.jp/site/chijiko/kichitai/tyosa/qanda_r2.html)

Yoshihara, Mari. 2007. Musicians from a Different Shore: Asians and Asian Americans in Classical Music. Temple University Press.

Yun, Isang and Luise Rinser. 1981. 『傷ついた龍:一作曲家の人生と作品についての対話(Injured Dragon: Dialogue on the Life and Works of a Composer)』Translated by Ito Narihiko. 未来社.

———————————–

Asia Orchestra Week 2022

2022/10/5-7 Tokyo Opera City Concert Hall

2022/10/5

<players>

Manila Symphony Orchestra

Conductor : Marlon Chen

Cello : Damodar Das Castillo

<pieces>

Lucio San Pedro:Lahing Kayumanggi

Elgar: Cello Concerto

Prokofiev : Ballet Suite from Romeo and Juliet(Marlon Chen Selection)

2022/10/6

<players>

Ryukyu Symphony Orchestra

Conductor : Otomo Naoto

Traditional Okinawan music and Ryukyu dance : Okinawa Prefectural University of the Arts, Ryukyu Performing Arts Major Alumni Association

Piano : Hagiwara Mami

<pieces>

Nakamura Toru : KAJADEFU For Ryukyu Traditional Music, Classical Dance and Orchestra

Haginomori Hideaki : Commissioned Work by the Ryukyu Symphony Orchestra

― To celebrate the 50th anniversary of Okinawa’s reversion to Japan

Ravel:Piano Concerto in G Major

Tchaikovsky : Symphony No.5 in E minor, op.64

2022/10/7

<players>

KBS Symphony Orchestra

Conductor : Hankyeol Yoon

Violin : Bomsori Kim

<pieces>

J. Strauss II: Overture <Die Fledermaus>

Bruch : Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor, op.26

Isang Yun : Symphony No. 2 (1984)

―――――――――――――――

KANOH, Haruka

Postdoctoral Fellow, Graduate School of Social Sciences, Hitotsubashi University. PhD (Social Sciences). Major in area studies (Vietnam), musical culture studies, global studies, etc. She stayed in Hanoi when she was a graduate student for her research. She has conducted research in a multi-disciplinary way on the relationship between art and politics, especially through “classical music.” Her postdoctoral dissertation is “Opera in Socialist Vietnam” (2021).